Lynwood’s Worst Nightmare

The Vikings terrorized Lynwood residents for years. The residents fought back.

The Vikings terrorized Lynwood residents for years. The residents fought back.

LEA ESTE ARTICULO EN:

Part of A Tradition of Violence, an extensive investigation into more than five decades of abuse, terror, and murder carried out by gangs within the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department.

Content Warning: This series explicitly details acts of violence (including murder) carried out by law enforcement officials. Please exercise self-care and check in with yourself before choosing to read.

There are at least 24 gangs within the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department. Officials at various government agencies, including the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors, the Los Angeles County District Attorney, the California Senate Senate Subcommittee on Police Officer Conduct, and the United States Commission on Civil Rights have heard testimony on the violence inflicted on communities at the hands of deputy gangs for decades. Deputy gangs have killed at least 40 people, all of whom were men of color. At least 10 of them had a mental illness. Los Angeles County keeps a list of lawsuits related to the deputy gangs. Litigation related to these cases has cost the County just over $100 million over the past 30 years.

Under section 186.22 of the California Penal Code a criminal gang is described as any organization or group of three (3) or more people that

1. has a common name or identifying sign or symbol,

2. has, as one of its primary activities, the commission of one of a long list of California criminal offenses, and

3. whose members have engaged in a "pattern of criminal gang activity" … either alone or together.

Sheriff's gangs fit the description.

Despite requests, the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department did not provide comment to Knock LA for the series.

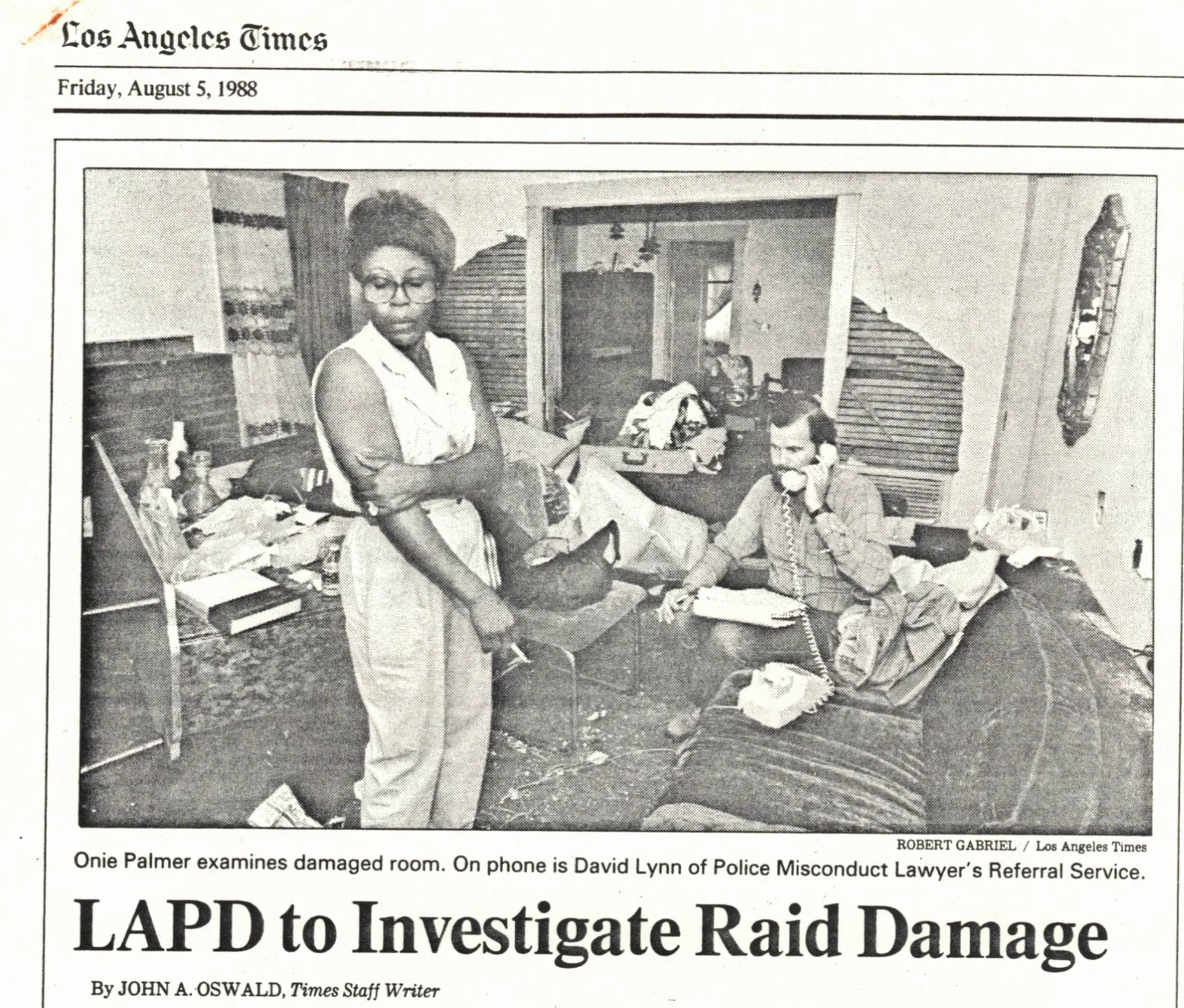

In the early 1990s, few law firms were willing to take on cases of police misconduct. John Burton, President of the Board of Directors of the National Police Accountability Project, said that “it used to be you just couldn’t sue the police. The legal doctrines weren’t really working or the juries were just so tough on you.” But a small collective of dedicated lawyers formed the Police Misconduct Lawyers Referral Service. The group cut their teeth representing the victims of a violent drug raid conducted by the Los Angeles Police Department in Southwest Los Angeles in 1988. Burton, a former PMLRS member, said that after settling the case, the group resolved to keep challenging law enforcement’s unchecked power. David Lynn, who sat on the board of the organization, quickly recommended that the group pursue litigation against the sheriff’s deputy gang in Lynwood – the Vikings.

Viking members and associates launched a violent campaign against residents of the Lynwood area. At least 30 people saw their homes ripped apart as they were held at gunpoint by deputies. At least 100 people suffered lifelong trauma. The Vikings subjected a disproportionate number of Black and Brown Angelenos to criminal activity under the guise of law enforcement. PMLRS began gathering claims for a landmark civil rights case: Darren Thomas v. County of Los Angeles.

The following deputy attacks were brutal. Knock LA is printing clinical terms described in the Darren Thomas case to illustrate the severity of the Vikings’ conduct.

All charges against Polk were dismissed at a preliminary hearing. Motivated by the outcome in his case, Polk, a half Black, half Latino man, was instrumental in helping community members share their stories of abuse at the hand of sheriff’s deputies with the attorneys at PMLRS.

Soon the Leonard family, who were white, approached the group. On February 10, 1990, William Leonard was shot and killed by Deputies Allyn L. Martin, Todd L. Wallace, Gerald R. Thompson, Chris J. Young, Timothy E. Benson, Scott L. Mccormick, Ronald E. Gilbert, Abel A. Moreno, Byron G. Wainie, Robert Blume, Steve Blair, John A. West, Stephen Downey, Neils Gittisarn, and six unidentified deputies.“ [Leonard] was shot 27 times, unarmed, and witnessed by his teenage daughter,” Lynn says. “From that interview people just started lining up and following this story to what happened to their relatives or to their neighbors,” Lynn says.

The first happened at or near the 5100 block of Beechwood as six unidentified deputies stopped, detained, and arrested a Latino man named Fernando Martinez. During the arrest, the deputies shoved Martinez’s head into the side of the deputies’ vehicle until the window cracked. Martinez was denied medical attention following the incident.

Just two blocks away at 11144 Virginia Avenue, Deputies Mann, Nordskog, John Chapman, Gary Blackwell, Michael Wilber, Lance Fralick, Juan Alvarado, and four unidentified deputies dragged Jose Ortega, a Latino man, and Aaron Breitigam, a white man, off the front porch. The deputies hit the young men repeatedly in the back with a metal flashlight. Both were released at the scene, and the officers left. A neighbor who witnessed the beatings called in a complaint to the Lynwood Station, and the unidentified deputies returned under the direction of Sergeant Yarborough. They took Ortega to St. Francis Hospital for x-rays and treatment for his injury. At the hospital, Ortega was greeted by Mann and Nordskog, who promptly arrested him. Instead of receiving medical treatment, he was charged by the District Attorney and prosecuted.

Deputies Dan Raimo, Timothy E. Benson, Kevin Goran, Brian Steinwand, John Corina, Joseph Holmes, K. Wall, Nelson, and two unidentified deputies entered and ransacked the shop. Washington’s safe, auto diagnostic computer, tools, equipment, and files were damaged. As they tore the inside of the shop apart, the deputies held guns to the heads of Holliman and Williams. Deputies kicked them both, pushed Holliman’s face into the ground and stomped on his hand, dislocating his thumb.

In one incident, Deputies James Whitten, Richard Calzada, Daniel Cooper, Robert Windrim, James Pacina, James Corrigan, Timothy Glover, Frustino Delvalle, John Chapman, Lieutenant A. Herrera, and several unidentified deputies served a search warrant at the Maya family home. The deputies held the Latinx family of nine at gunpoint while their house was torn apart. Five of the deputies took Carlos Maya into custody during the search and beat him at the Lynwood Station.

Half a mile south, Deputies Craig Ditsch, Frank Gonzales, Kevin Goran, Joseph Guzman, Rodolfo O’Dell, Daniel Raimo, Martin Rodriguez, and several unidentified deputies forcibly entered another home to execute a search warrant. The deputies held the Latinx family of eight inside at gunpoint, including a woman bedridden following a recent surgery. Deputies lifted her out of bed and forcibly moved her around the inside of the home. Nearby, Sergeant Anderson, Deputies Robert Rifkin, Giron, Holbrook, Nunez, Brandenburg, Costleigh, O’Hara, and several additional unidentified deputies accosted another Latino man, Sergio Gallindo. The deputies raided Gallindo’s house just as other deputies had done to the Maya family.

One mile away, Deputies Gregory Thompson, Brian Steinwand, Jack Neihouse, Sergeants Tommy Harris, Javier Clift, John Corina, and several unidentified deputies forced their way into a third home. They held another family at gunpoint as they destroyed the victims’ home. Nearby, Deputies Albert Grotefend, Raymond Esquerra, Michael Salvatore, Jack Ramirez, Ruben Gracia, William Roman, Scott Carter, and Richard Orosco, along with several additional deputies, held the Tovar family, who were also Latinx. Just a few houses down, Deputies, Scott Carter, Esquerra, William Roman, Richard Orosco, Jack Ramirez, Michael Salvatore, Ruben Gracia, and several additional unidentified deputies pushed their way into a fourth home, the Calderon family residence. Some deputies held the Latinx family at gunpoint while other deputies tore through their belongings and seized a rifle lawfully owned by one of the residents. Later, it was returned in a damaged and inoperable condition. Ruben Calderon was attacked by Deputies Curtis Golden, Danielle Cormier, Allen Ripley, Kelly “Gill” McMichael, Douglas Gillies, Lieutenant Radeleff, Lieutenant Richard L. Castro, and 11 additional deputies. Also among them was Deputy Byron G. Wainie, who shot and killed William Leonard two months prior. They choked Calderon with a flashlight, slammed a car door on his legs, and arrested him. Once he arrived at the Lynwood Station, he was beaten again. His mother called to complain about his treatment, and the deputies responded by threatening him and launching into another beating.

Deputies Douglas Gillies, Kevin J. Kiff, Kelly (Gill) McMichael, Katherine Brown-Voyer, Michael Voge, John Mossotti, Jack Tarasiuk, Loy Luna, T.J. Harvey, R.A. Reed, and several additional unidentified deputies struck and beat Latino men Sergio Sanchez, Alfredo Sanchez, Alfonso Sanchez, and Jose Sanchez with batons and flashlights. Estela and Marta Velez, who was eight months pregnant, were assaulted as well. Yldefonza Lorenzana, an 82-year-old great-grandmother, was held for the duration of the detention at the point of a shotgun while she lay in her bed. Richard Hernandez, a Latino man, met the same treatment that day by Deputies T. Running, T. Brownell, Timothy E. Benson, Kevin J. Kiff, and five additional unidentified deputies.

The deputies took Gonzales away from nearby family members and beat him, causing serious injuries to his head and body. They then imprisoned him for 10 days. The next day, Deputy Luna and 12 additional unidentified officers detained and arrested Jesse Melendrez and beat him in the back of their patrol car while he was handcuffed. Then they brought Melendrez inside, handcuffed him to a swivel chair, and continued beating him.

Sergeant Devine, Deputies Allen Harris, Robert Delgadillo, and four other unidentified deputies arrested Martinez in Ham Park, a little over two months after his first arrest. According to the lawsuit, a deputy drove recklessly while Martinez was handcuffed in the back of a patrol car, causing his head to smash into the metal partition separating the front and back seats of the vehicle. Once Martinez arrived at the station, deputies beat, choked, and kicked him.

Both men were beaten in the face. One deputy shoved a loaded revolver into Ochoa’s mouth and told him, “Every time you see us we are going to fuck with you.” Indeed, just three days later, nine deputies stopped Preciado and Ochoa again. Preciado was kept in a dark cell and beaten while Ochoa’s house was raided without a warrant, according to the lawsuit.

While en route to the police station, the deputies drove recklessly to cause Thomas, Sterling, Marshall, and Scott to fall into the hard surfaces in the back of the squad car. Once they arrived at the Lynwood Station, the men were taken into the “gang trailer” and beaten, according to the lawsuit. Thomas was kicked in the face, choked into unconsciousness twice, and electrocuted with a taser. Marshall had a shotgun held to his head. Throughout the beating, the deputies told the men, “Yeah n*****, you ain’t got no rights. We are going to make sure you don’t ask any more questions!” The deputies filed reports with the District Attorney’s office falsely stating that Thomas was drinking an alcoholic beverage on a public street, and incorrectly stated that drinking an alcoholic beverage on private property in public view was a violation of a Lynwood ordinance. Thomas was charged with battery on an officer and prosecuted. One year later, the charges were dismissed in a mistrial.

Just over a week later, Deputies Brian Steinwand and Dan Raimo opened fire on Tracy Batts as he traveled down Atlantic Avenue. The deputies said in their reports that Batts was armed. According to the lawsuit, this was not true.

Two weeks after Johnson’s death, Nordskog, Kiff, Cormier, Mann, Patrick Valdez, and Michael Schneider detained and arrested Ron Dalton, Eric Jones, and Marcelo Gonzalez. They beat all three men, and one of the deputies shoved a loaded revolver into Dalton’s mouth and threatened to blow his head off. Another deputy put a gun to Gonzalez’s head and pulled the trigger, but the gun did not fire. The three men saw charges filed against them, but all criminal charges against Dalton and Jones were dismissed.

On May 25, 1990, Deputy Raimo made another attempt on Tracy Batts’ life. Deputies Pippin and Gregory Thompson of Lynwood and J. Leslie and J. Sheehy of the Firestone Station, along with several unidentified deputies, joined Raimo. According to the lawsuit, Raimo and Thompson falsely informed the others that Batts was armed and dangerous. After a couple of hours searching, Pippin found Batts and shot him in the right leg. After Batts fell, Deputy Leslie instructed Compton police officer Zampiello to unleash his attack canine on Batts’ injured leg, mauling him.

Archambault falsely stated that Coleman unlawfully possessed and brandished a gun. According to the lawsuit, the deputy falsified evidence during the investigation. Coleman was charged, but fully acquitted the following year following a lengthy trial. Gary Casselamn, who was on Coleman’s legal team, says he received a note from the jury reading, “The deputy ought to be in prison.”

The case was met with skepticism by the local press, and many of the victims’ stories were ignored or forgotten. At the time, many held the belief that police and district attorneys could do no wrong. “Many DA reviews of shootings, they whitewash bullshit,” says James Mueller, a civil rights attorney. “It’s not in their interest to challenge law enforcement. The problem is much bigger than anybody says.”

Some were affiliated with two local street gangs, Lynwood Mob and Young Crowd, who were at war with each other and under attack from the Vikings. In order to get all of the plaintiffs on the same page, Lloyd Polk, who achieved the status of an older, respected member of Young Crowd at just 21, organized a meeting with representatives from each gang to work out a truce in December 1990. The meeting took place at David Lynn’s home and was a success, but the victory was short lived. “When he got home and was saying goodbye to his homies, a car drove up slowly and opened fire.” Lynn says. “Lloyd Polk was shot in the chest and killed. This deputy came around the corner and with his lights off and just sat there. He got out of his car and started walking up and everybody’s like, ‘He’s been shot! He’s been shot!’ He just kind of slowly went back to his car and sat there.”

The explorer program is billed as a career development curriculum for young adults. “She overheard deputies planning a hit. That night he was killed, they made it look like a drive-by shooting,” Lynn says. He interviewed the explorer, Anietra Haley, a dozen more times about what she heard on tape. Lynn asked his deputy sources, some of whom were Vikings, if the deputy gang engaged in those activities. A deputy source said a system was in place for drive-bys committed by other law enforcement officers. “This deputy who had been involved in other drive-bys at the time said they put a deputy around the corner to come in and control the scene after the shooting deputy has left.” That technique matched exactly what Lynn witnessed during the Polk shooting. For the first time, Lynn was unsure of what to do next. “We didn’t know what to do with something like this. Who do you call? So we took it to the FBI.” His team was livid. “I said, ‘You can’t trust those people,” Burton says. The FBI developed Haley as a source which Burton says, “Became a whole drama.”

The Sheriff’s Department charged that Lynn induced a former sheriff’s cadet, Anietra Haley, into concocting a story implicating deputies in the December 1990 drive-by shooting death of Lloyd Polk. Gloria Clark, Polk’s common law mother-in-law, told reporters that Haley recanted her story because investigators threatened to send her to prison for 26 years if any deputies were convicted. The FBI and US Attorney’s office began a grand jury investigation into Lynn, which turned up nothing. The lawyers pursuing the federal case issued a statement about the investigation, claiming it was a means to intimidate witnesses and discredit their case. They continued that Lynn’s “only crime was naivete – believing that the FBI would act in good faith on information that Los Angeles sheriff deputies plotted and carried out the shooting of a civil rights plaintiff.” The attorneys also released previously-sealed audiotapes and transcripts of Lynn’s interviews with Haley which corroborated his account. On the tapes, Haley expressed frustration that her FBI handler ruined attempts to secretly record incriminating statements from one of the deputies involved in the shooting. Haley also told Lynn that the same FBI agent was sexually harassing her.

“I couldn’t believe that the US attorney and the FBI were actually coming after me, the only investigator on this civil rights case,” Lynn says. After he learned about the grand jury investigation, Lynn waived his right to remain silent and submitted to a three-hour interview with the FBI and an assistant US attorney, according to Burton. Meanwhile, Haley pleaded guilty to providing false information and was sentenced to probation.

Polk had a young son at the time of his death. Fifteen years after his father’s death, Lloyd Polk III was subjected to harassment because of who his father was. “Polk’s son was cornered in an alley behind where he was living,” Lynn tells Knock LA. “[He] was told by two deputies we know who your father was and we just want to let you know, we know who you are.”

Even though Sheriff Block publicly maintained that gangs were harmless social clubs, the federal court begged to differ. In October 1991, US District Judge Terry J. Hatter Jr. issued a preliminary injunction directing the 8,000 officers and 4,000 other employees of the Sheriff’s Department to abide by department regulations, particularly those dictating when deputies can use force and how to conduct searches. In his finding Hatter wrote that a “neo-Nazi, white supremacist gang” of deputies exists while “policy makers” in the department “tacitly authorize deputies’ unconstitutional behavior.”

Deputies at the Lynwood Station remained incensed at the exposure and sought revenge on Lynn. One of Lynn’s contacts warned him that he had heard a deputy ask, “Wouldn’t it be bitchin’ if someone killed David Lynn?” In turn, he began to fear for his life. “I started carrying guns, and I didn’t have a permit to carry a gun,” he says. Loy Luna, a deputy implicated in several of the incidents in the lawsuits, began threatening and attacking Lynn in the street, even shooting at him while he was near a park with some members of Young Crowd. “Luna came by, kind of mad-dogged us and drove around on the dead end at a park, and all of a sudden a shot came over our heads,” he recalls. “We all went down to the ground. Everybody’s grabbing their guns. We don’t know who was shooting at us.” Later, a bystander informed the group that the person shooting was a sheriff’s deputy. He was also known to wear a raid jacket with “SHERIFF” printed across the back, carry his badge at his waist, and drive a white unmarked four-door Chevrolet with a government “E” plate (the video shows a vehicle matching that description).

Lynn believes Luna shot Lloyd Polk. “I’ve never told anybody something about what happened there,” he tells Knock LA. “A witness who obviously has never wanted to come forward did tell me that they did identify people. Luna’s the shooter… and the driver was Jason Mann.” However, Luna never saw any punishment for this crime. According to TransparentCA, Luna retired in 2016 and receives over $200,000 each year in pension. Lynn says he still receives complaints about Luna.

On May 7, 1995, 24-year-old Jose Nieves was shot in the back during a botched raid. Nieves was also a witness to one of the incidents documented in the federal lawsuit. Five days later, Young Crowd member Freddie Fuiava shot and killed Lynwood Deputy Stephen Blair. At Blair’s funeral, sheriff’s deputies passed out lapel pins bearing the Viking symbol, according to former Deputy Mike Osborne. Just one month later, the federal trial began.

The case went to a jury trial and focused on Darren Thomas, who was taken from his home to the Lynwood Station and beaten. The County moved to settle, and the plaintiffs celebrated their victory. They were awarded $7.5 million with an additional $1.5 million earmarked for sheriff’s department reforms. The Los Angeles Times reported several weeks later that attorneys for the County estimated that if all the class action Lynwood cases went to trial, the potential damages and attorney fees could have reached $18.9 million.

The Lynwood Station closed in 1994, but was replaced by the newly built Century Station. The injunction Hatter issued was blocked by the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals and later reversed. “It was not a well-crafted injunction which made it harder for us to defend on appeal. He wanted to do things his way,” Burton says. “There’s still way too many shootings and it’s tolerated, I mean. You know, from the time they roll out the investigators on, it’s just to cover it up.” His colleague James Muller agrees. “Obviously, 30 years ago there were definitely gangs and now there are still deputy gangs. But for me, it’s all bricks in the wall.”

The litigation did not act as a deterrent for the Vikings. Rather, they were emboldened. The department did not adopt any significant reforms, and many of the Vikings were promoted and moved to different jurisdictions. Now the gang had the opportunity to share its tactics with more deputies and bring others into the fold.

READ NEXT: The Miracle Trial